You might be wondering why I’m posting weather conditions on Facebook these mornings. The comments probably give it away, but I’ll say it clearly now: Our father Antonino a/k/a Tony a/k/a Nuccio (depending on what language you speak) passed away early last week. He used to begin his day with coffee and firing up his iPad to post the weather report on Facebook.

Tony—he anglicized his name like lots of Italian immigrants in the 1950s—was 91, nearly 92 years old and suffering terribly from a bunch of ailments. He may have been approaching 100 but he wasn’t a stranger to technology. He kept in touch with his world via Facebook posts and videochats with family in both the U.S. and Italy. The chats were his lifeline to a world he couldn’t be in any more, and in a way showed us the curious, always learning kind of guy that he was.

I can only write snippets that I hope give an idea of my dad. I loved him, sometimes argued with him, but always felt that I had this gentle spirit watching over me. And it wasn’t just us—my sister and brother , our families, and the seemingly dozens of people he cared about. With such a long life, it would be foolish for me to document everything, but I’ll try to give you a sense of him and how he (along with my mother) affected the lives of so many people.

I was his firstborn, so I got his youth and enthusiasm. One of my earliest memories is of the back of his head. We were at some church fair in East New York, Brooklyn, and he was carrying me on his shoulders. It was nighttime and if I close my eyes I can still see the ferris wheel, the colored lights, and maybe (hey, I was maybe two or three years old) an elevated train passing in the distance.

We used to spend a lot of the summer at my maternal grandparents’ bungalow near New Dorp Beach. Another fuzzy memory. We’d go to the beach, just the two of us. He’d sit me down on the sand and tell me, “Don’t move. Watch me.” He’d peel down to his bathing suit and dive into the surf. A strong swimmer, he went out so far that he was only a tiny dot on the horizon. He’d swing his arms to show me he was still there, and then swim back to me, pick me up, and swing me around. He taught me how to swim in those waters by body surfing. Once I learned how to ride the waves, the rest was easy.

He created a perfect backyard for his kids and wife. We had a pool, a picnic table, a barbecue, and a big vegetable garden. He tasked my cousin Dominick and me (maybe I was four?) and my red wagon to go into the woods in back and ferry truckloads of the rich soil there to spread on the garden. As a little kid, I always had a patch in that garden. I grew cucumbers, radishes, and peas. Tony (as most people called him) grew: tomatoes, corn, Sicilian squash (“cucuzza”), lettices, eggplant, swiss chard, and whatever else he might have seen at the garden center.

He lived at the hardware store and garden center on weekends. Our little house was a constant DIY project. Most projects went well. Some didn’t. He used a woodburning stove to heat a patio that had turned into a greenhouse. He and my mom did some Saturday morning errands, leaving us sleeping at home. The greenhouse roof caught fire and a neighbor called to tell me. It was the first and only time I pulled the fire alarm up the street.

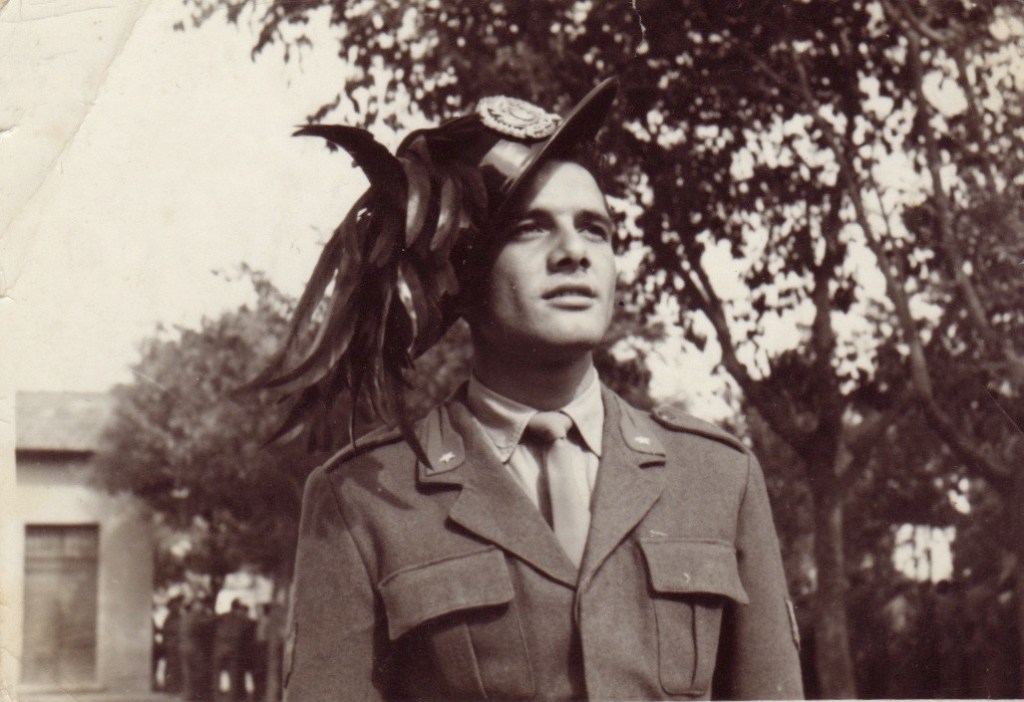

They tell me he was a bad teenager who skipped class and my grandparents sent him to army school (this is back in Italy) when he was 17. You can still see one of his Sicilian separatist graffiti on the side of an apartment building on Palermo’s Corso Calatafimi. I’ve never seen pictures of him as a child—I’m sure that the disruption of World War II played a role—but there are lots of photos of him in the Italian army and school. Most of the time he looks confident and strong, posing in a typically Italian male way (you know it when you see it). I doubt that he had any idea of what his life was going to be like back then. He regaled us regularly with tales of his adventures, but one story sticks in my mind. He’d get bored of a base, or a city. So instead of trying to get a transfer—I’m not sure that was even possible—he’d write his mother, who had a cousin in the defense department. Nuccio would tell his mother that he found the most wonderful girl and that he was ib love. Transfer orders came quickly.

A lot of what he did and became had to do with his being an immigrant. My father spoke until his last breath with a fairly heavy Italian accent. He wasn’t studious in the conventional sense, but he was always curious and read the paper every day. He had the usual Sicilian speaking English accent. He had trouble with double consonants in words like “doctor.” And Siri did not understand him. But he also had a gift for mangling common expressions. My favorite was “you must cry the consequences.” I always thought that it would be a great title for either a country or Elvis Costello song.

I was never sure, though, if he really understood how the U.S. is governed. He looked at its politics through the eyes of a European, and was always frustrated by what he thought of as sheepish compliance by his fellow citizens. Our dinner table when I was a teenager was often a battlefield with my mother, the good liberal, trying to mediate while her hotheaded son and husband butted heads. I knew, though, that he enoyed arguing with me. We never really got angry with each other. In fact, props to him for what was an incredible tolerance. Unlike a lot of my friends’ parents, he never butted in and tried to control our lives. At the same time, he and our mom always supported the habits of their brood; my father and I spent hours playing with and repairing tape recorders, radios, and stereos.

If Nuccio never quite “got” the U.S., he mastered, again with my mother, the art of hospitality. And he gave us a pretty exotic childhood, with Italians visiting and staying over. We lived on a street full of immigrants, and I got used to hearing different accents, languages, and dialects. Way before Giorgio Armani defined how people should dress, we somehow thought that having a Sicilian father was cool, and that people whose families lived in the U.S. for generations were somehow not as lucky as we were.

In the last couple of decades, my dad wasn’t a part of my daily existence. He moved to Pennsylvania and I’ve lived part of the year in Italy. Still, we kept in touch, especially the last few years, with FaceTime. He’d tease me if I needed a shave or if my plants obviously needed TLC. I’m realizing now how a lot of my life choices, like where I live, and which passport I use the most, was an effort to please him, even if he never told me what to do. Daily caregiving recently fell to my sainted sister; they could bicker like an old couple. But even if I didn’t see him that often, I’ll miss knowing that this sweet, complicated and loving guy was just a click or car ride away. We’ll all miss him terribly.

Photo on top: My father Nuccio on the right with his brother and Skype video chat partner Ignazio, in Palermo, November 2003.