I was not about to go near The Spartan Woman. She was just a few meters away cursing at the food processor and Martha Stewart last week. It’s not that she had beef with Martha—quite the contrary. It’s just that she was trying to bake one of Martha’s recipes, a lime tart, and had to convert such quantities as “one stick of butter” or “half a cup of …” into the metric measurements we use in Europe. [TSW hastens to tell me that it’s not just the system of measurement but how recipes in the U.S. are written, often giving less accurate volumetric quantities rather than the weights professional chefs and Europeople use.]

She wasn’t alone. Expat message boards are full of posts with people having trouble either converting measurements or finding ingredients that may be common in the United States—vanilla extract, for example—but hard to find in Italy. And measurements? Fuhgetaboutit.

As someone with a foot on both continents, I think about these differences a lot. And language, though it’s often a big barrier for newbies in a new country, isn’t the only one. I’m talking about measurements, more specifically, the metric system. The difference between the American version of Imperial measurements and the metric system might be harder to get over. Think about it: An American’s whole frame of reference to the world around us involves measurement of some kind. Two miles, 30 feet, 5,000 feet altitude, 45 degrees, 14 inches, a pint.

The United States is almost alone in the world in clinging to this obsolete and strange system. The other countries? Those progressive nations of Liberia and Myanmar. I call the system strange because, well, it is. Think about it: 5,280 feet equals a mile.Thirty-six inches, a yard; 12 inches, a foot. The only halfway sane one is the ton—at least 2,000 pounds is an easy number to remember.

Talk about American exceptionalism.

Seriously, though, one of the biggest barriers to improving life in the United States is the general refusal to learn much from the rest of the world in a conscious way. There’s almost always the assumption that Americans do it better, have it better, know more. And the U.S. way of measuring and perceiving the world is almost unique, and makes Americans nervous when they venture abroad. Or even over the borders to Mexico and Canada. I’m sorry, but Liberia isn’t exactly leading the way, and Myanmar is currectly ruled by a vicious and genocidal military dictatorship. Not great company to keep.

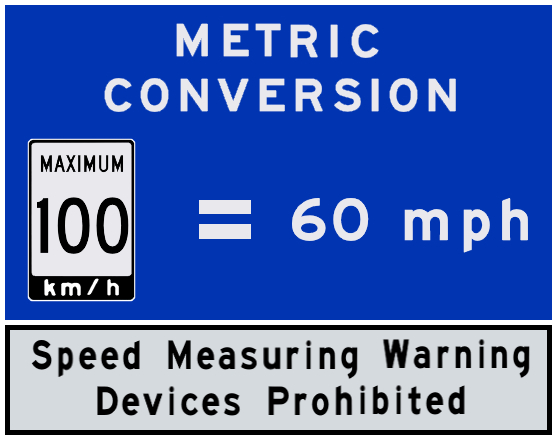

Inertia to change certainly plays a part. And so does math. When I was a kid in the 1960s, the U.S. made baby steps toward metrification. But instead of instilling in schoolchildren the system from scratch, teachers and texts taught equivalents. One pound equals 454 grams; to convert Celsius to Fahrenheit degrees, follow the formula temp Celsius X 1.8+32′ degrees=temp F. Lunacy, Why bother?

Maybe this sounds trivial, but think about it. You’re on your first trip abroad, to, say, Paris. You look at the TV weather channel in your hotel room, trying to figure out how to dress, and you see that it’s 12 degrees outside. What’s better? Plugging in the variables? Or knowing that 12 degrees is a chilly spring or autumn day? Sure, now you just look at your phone, but doing so isn’t teaching you anything, or making your more comfortable with how the rest of the world perceives temperatures.

BUT CLINGING TO THE OLD SYSTEM ISN’T just about inertia. Radical right wingers have made it one of their causes. Check out this video by that great intellectual Tucker Carlson. Back in 2019 he interviewed New Criterion editor James Panero about “the tyranny of the metric system.” I love how Panero calls U.S. measurements natural, metric ones abstract—and then dismisses the fact that we have 10 fingers and 10 toes, and how the metric system is based on….well, 10.

Despite this know-nothing astroturf nonsense, and popular fears, American industry knows better. Have you looked at a bottle of wine or soda recently? You’ll see 750 ml, 1 liter. Buy a car, or even a big American SUV lately? Your engine is 2.0 liters, 3.5 liters, etc. The dependably capitalist economic system has already made the change and I’ll bet Carson and Panero would call our leaders of industry woke socialists.

Getting with the program may be hard at first, but it’s not impossible. Canada switched from Imperial measurements to the metric system on April 1, 1975, and within a generation Canadian young people are fully immersed in metrics. A friend of mine from Toronto says she’s confused when she sees Fahrenheit degrees, and while she lived in the U.S. for a few years, she finds feet, yards, and miles to be impossibly strange.

So what do you do to get in synch with the rest of the world? I’m not saying that you should live in a metric bubble when everyone around you is in a real-life Flintstones episode. Just get acquainted with what everyone else uses, so that if you venture past the U.S. borders you won’t be lost. Start simply. Change the settings on your phone to metric measurements. You’ll get used to a kilometer and the Celsius scale. Or just remember that a kilometer is a little more than half a mile, give or take. And Celsius is easy, especially for landmarks of 0 degrees and above. Zero is freezing; 10 is a cool spring day; 20 is room temperature; 30 is a nice but not sweltering day at the beach. And 37 is body temperature—and a sweltering day at the beach.

The system of measurement isn’t the only thing keeping Americans in a bubble. In the rest of the world when it comes to politics, red means left wing, blue is conservative/right wing. But that’s another post. Be brave, America! You have nothing to lose but your disorientation. And you’ll know that when your phone tells you that it’s going to be 31 degrees this afternoon, it’s a great day to head out to that beach.