IF YOU READ last week’s post, you’ll know that we went to New York and back for the holidays. What I mostly left out is what we did there. Why? I’m still processing a couple of things, as they say. And in the past week or so at home here in Italy, we’ve been busy restarting our lives here, shopping for food, buying a huge pile of wood for the fireplace, getting medicine refills, etc.

I’m still finding it a little astonishing that I took my first vacation in my native New York. We’ve been buying round trip flights from here for awhile, ever since the airline Alitalia folded its wings. But then we stayed back in NY for a few months. This time it was for a scant few weeks and we definitely were visitors this time, staying at a relative’s home and borrowing a car we’d given up.

One of the things that happens during the holiday season (and pre-trip) is that you have to eliminate items from your to-do list. We started out with an ambitious to-do-before departure list and had to cull as we went along. I’ll get into that later, but the process led to our spending more time getting stuff done in New York. Unpleasant but necessary tasks, that is.

With all that in mind, I’ve been trying to figure out how to organize this so it’s not just a rant about reverse cultural shock. There’s too much of that floating around online. (Hey, I’ve had feet planted in two places for so long I’m immune.) The Spartan Woman suggested the following approach:

THE GOOD

REMEMBER WHEN PASSPORT agents were surly and acted as though you were a criminal for daring to leave the country? That’s changed, at least in our experience. Maybe it’s down to our being old? I don’t know, but suddenly ICE is hiring friendly people. Or, just maybe, we’re of a certain age now and don’t look like the kind of people US immigration wants to keep out.

In any event, it was a good way to ease into the U.S. Better still was seeing our grownup kids again. Daughter no. 1 gave us a new addition to the family, a bouncing (literally) baby boy. No pictures, sorry. We’re keeping the child out of social media, at least for now. I may be a proud nonno (grandpa), but The Boy is objectively really good looking, and appears to have inherited some of his mom’s impishness. You’ll have to take my biased word for it. And though we moved, it was good to see some neighbors, and comical to see others, like the wild turkeys that have taken over the island.

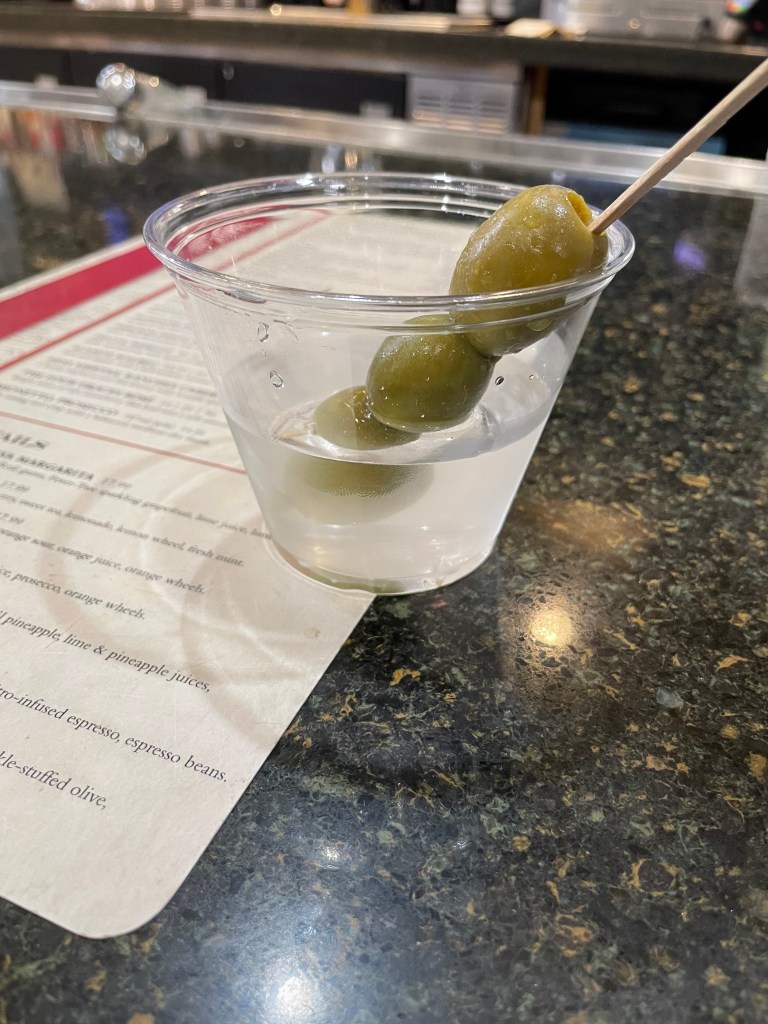

One thing we miss when we’re in our Umbrian mountain retreat is multiethnic food delivery. Even on Staten Island, which is often depicted as a bigoted white people hellscape. The truth is more subtle than that, and the island’s North Shore is a paradise of ethnic restaurants. In our short time there, we ordered from Chinese, Vietnamese, Turkish, Thai, and Mexican places. We didn’t have time to have the Sri Lankan food we love.

While we’re on the subject of crazy choice, Costco? I know, I know, where have I been? I finally was initiated into the cult by Daughter No. 1, just for one visit. I was overwhelmed. Not that we bought that much—we had specific goals. It wasn’t so much the crazy amount of merch for sale, even though I saw everything from espresso machines to solar panels to yoga pants to flats of every household item imaginable. But wow, in the space of less than hour I heard at least half a dozen non-English languages. That the company is fairly humane in its personnel practices compared to other giants of commerce added to my not hating it. Buon lavoro, Costco.

I did notice one other thing immediately. As soon as we cleared customs and were in a taxi headed to our kid’s home, I pulled out my phone and wow, this 5G thing. I’d forgotten how fast it is, at least the T-Mobile version of it, and later tested it to be, in some places, a 600 mb/s download. That’s fast. And our kid has, like we did, 1 gigabyte/second fiber. Fast fiber internet has made it to Italy in general, and our town of Valfabbrica specifically. But not in the rural areas. We use a local provider here, which gives us download speeds of around 30 mb/s, which isn’t bad considering it’s wireless. But a guy can get spoiled. Still, I wouldn’t trade my life for fast downloads. Yet.

THE BAD

OH BOY, THIS. Before we left for New York, we’d wanted to get a Covid booster shot, since the latest one covers the latest known variants. Here in Umbria, you go onto the public health website and look for a location and convenient time and hit the send button and show up for the shot. But we ran out of time and figured we’d get the shot at our former local pharmacy in New York.Unfortunately, Nick up the street wasn’t handling the vaccine. So we had to look at the local megaeverythingwithpharmacy places like CVS and Walgreen.

The closest CVS told us they were out of the stuff and maybe were getting some in the future. But Walgreen’s website said make that appointment. I went through the online scheduler and completed the online medical history/consent forms for the two of us.

The day arrives, we drive a couple of miles. There’s a woman ahead of us in the vaccine line. She’s filling out the history form. “We did ours online,” I said. “I did too but they want me to fill it out here again.” The staff behind the counter is obviously overwhelmed, answering phone calls, taking in prescriptions and giving out meds to other customers. We wait and wait and wait. The nice woman in front of us was finally frustrated and disappears. They call her name, finally, to get her shot, and no one answers.

Finally, the harried clerk asks us to fill out the damn history/consent form. “I did it online,” I respond. “We’re asking people to do it here,” she says without giving me a reason. I refuse. “Sorry, I did it online and I’m not going to fill it out again. Look in your system.” There’s a standoff. Finally the overworked pharmacist tells her to dig it out of the computer. More waiting–at this point we’d been there an hour past our appointment time. We weren’t giving up. At last, the pharmacist come out and administers the shot: 75 minutes after our appointment time. We note that they have lots of people restocking the shelves with stuff like Doritos and deodorant, while the pharmacy workers look like hunted animals. American free enterprise at work.

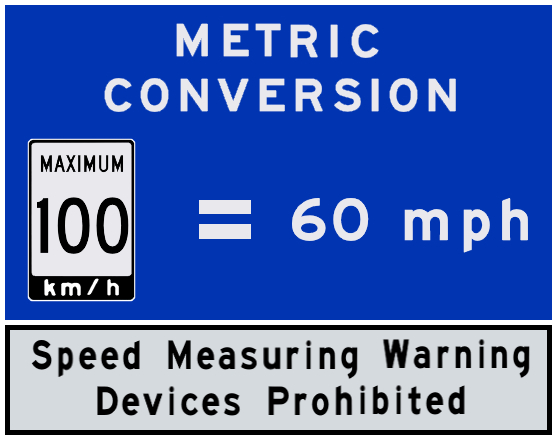

Finally we drive back. The main drag through that part of the island is a two lane road that was built in the 1920s and ’30s, with small shops and converted houses hosting insurance agencies and the like lining the street. But something’s out of whack. Big hulking SUVs and pickup trucks like Ford F150s dominate. It’s like the hippo dance in the Disney movie Fantasia. If the giants aren’t being driven like drunken Romans are behind the wheel, they’re creeping along because I’m sure their drivers can’t see out of them. Why do Americans need a tank to go to the drug store?

Another time I stop at a traffic light to make a left turn. One of the misplace macho drivers doesn’t think I’m moving fast enough (I am not a slow driver) and charges over on the right and without caring makes the left, causing oncoming drivers to hit their brakes. This happens over and over. All of a sudden driving in Italy seems sane.

THE MEH

LET’S TALK ABOUT prices, okay people? The U.S., once you’re been away, just seems like a giant machine designed to drain its people of their money. For instance, we buy Royal Canin dog food for our little prince Niko. It’s produced in plants around the world, but it’s a French subsidiary of the giant Mars Inc. In the U.S., a little over one kilo costs $21. The same food, but almost double the quantity, costs €21 in Italy, or about $23. The common excuse, er, rationalization is that wages are higher in the U.S. and so are fixed costs. But double? If you know, tell me why.

While I’m on the subject of allocating funds….I get it. New York is constantly being rebuilt. But sorry, what’s there can be so crappy. I traipsed about the Financial District for the best part of a day to take care of a bureaucratic matter. An Italian matter. (Don’t ask.) I used to work in the neighborhood and didn’t really notice before, but the streets are in crappy condition. Sidewalks are broken up, there are shoddy barricades everywhere and in general the place doesn’t look like one of the financial and media capitals of the world. I guess I’d taken the crappiness for granted before.

/rantover. Back to Italy after this.